Dr A P J Abdul Kalam, the all time favorite and one of the most beloved Presidents of this country, had once famously quipped: dreams are not what you see in sleep, dreams are what drive you to achieve your ambitions when you are awake.

I must admit, I seem to

have gone beyond. My dream, of seeing a transparent and accountable judiciary,

has taken me to a state of sleep deprivation or insomnia. Of late my wife has

been complaining about me talking in my sleep. The words she has recognized are

like ‘unfair’, ‘injustice’, ‘stupid’, ‘selfish’ etc.

That put me at a loss in

deciding whether I should continue with my question ‘who will judge the judges’

and assertion that ‘contempt of court is anathema in a democracy, democracy

demands Contempt of Citizen (Prevention of) Act’ or retire. Would it result in

the proverbial slip between the cup and lip? Or would it be like the proverbial

dog’s tail that can never be straightened?

Anyhow, when the debate

over the appointment of judges to the higher judiciary is heating up, I have

decided to take a break. For now I shall refrain from dealing with case laws

that question the credibility and integrity of the justice delivery system

headed by the judiciary.

Here I shall narrate how

the total failure of our judiciary has led to the collapse of the system of

governance itself. This is notwithstanding Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s fast

paced creation of infrastructure, generation of employment and access to basic

facilities offered to the marginalized.

The problem is with

delivery of government services, in its myriad forms, to citizens, in general.

I, for one, believe that the failure of the judiciary is being exploited by the

public servants in the other organs of governance and driving citizens to take

law into their own hands. It is now the proverbial question of which came first:

the chicken or the egg?

On 03/12/2022 the media

reported a tall claim- we are ‘most

transparent institution’- made by some judges of the apex court. The fact is

they are not. Absolutely not. Let us analyze it in the context of compliance

with the Right to Information Act.

The first and foremost

fact is neither the apex court nor the information commissions have complied

with the mandate of Section 4(1)(b) of the RTI Act whereby all public

authorities are required to disclose certain information about their structure,

employees, functions , remuneration, contact information, documents held,

procedure followed etc.

I usually seek information

on compliance with two of these- the directory of the public servants and their

remuneration- which are required to be disclosed under Sec4(1)(b) (ix) and(x). It is my simple yardstick for measuring the

transparency of any public authority.

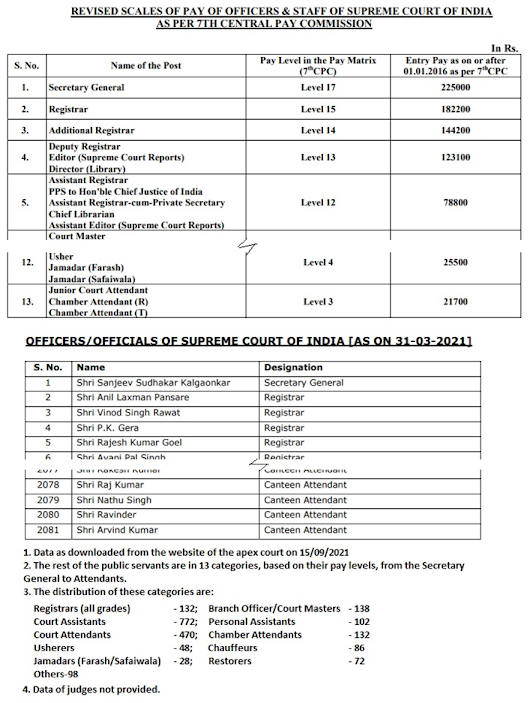

The data downloaded from

the respective websites of the Kerala State Information Commission (KSIC),

Central Information Commission (CIC) and the

Supreme Court (SC), are shown in

the screenshots 1 to 5 provided at the end of this part. The facts to be noted are:

Ø The KSIC had published the information correct enough

to pass muster till 2011

Ø The CIC had published the information correctly till

2012.

Ø The apex court had not published the information

pertaining to judges even in 2021.

Ø The CIC has reduced its disclosure to practically

nothing in 2022.

Ø The KSIC has totally done away with disclosures

mandated under Section4(1)(b) in 2022

Certain provisions of the

RTI Act appear to be designed to subvert the law itself. It begins with the

process of selection of the information commissioners. It is done by a

committee of three comprising the PM/CM, another minister from the respective

cabinet and the Leader of the Opposition. With the absence of a mandate for

unanimity, the Leader of the Opposition is just a dummy in the selection

process.

So far, I have come across

just one case of such a selection process being challenged. This happened when

a retired bureaucrat, P J Thomas, facing trial in the Palmolien Import Scam,

was appointed as the Central Vigilance Commissioner. The apex court set aside

his appointment in 2011. (But the case in which he is an accused is still

pending. The alleged offence was committed in 1992.)

More importantly, the

allegation of nepotism being hurled at the judiciary and its Collegium, is

relevant in the case of these appointments too. It is generally bureaucrats who

are closer to the power centers, who are seen making it as information

commissioners and members of other quasi judicial bodies.

Given the fact that the

task of the information commissioners is simpler than that of a munsif, the

status, pay and perks given to them make it lucrative as sine cures for

retiring babus; of course, at unwarranted and exorbitant cost to the exchequer.

The law has explicitly

barred certain information from being disclosed as well as kept certain

organizations, as a whole, out of purview of the RTI Act. With that, all that

the information commissioners have to do, on receipt of an appeal, is to ask

just two questions beginning with: have all the information sought, which can

be disclosed, been provided or not? If yes, have they been provided within the

specified time frame? If not, is there any legally valid reason for the delay

or denial? It is now for the information commissioner to get these reasons from

the Public Information Officer, through a show cause notice. In the words of

the law, be given a reasonable opportunity

of being heard before any penalty is imposed on him.

The penalty is also

specified-Rs 250/- per day of delay after 30 days of receipt of the

application.

However, what we find is

that even when the information commissioners order the PIOs to provide the

information that had not been provided, he desists from imposing the mandated

penalty. It leads not only to subversion of the law but also to financial loss

to the State. Worse, apprehensions of corruption also become wholly justified,

not only in the broadest sense that Advocate Prashant Bhushan meant while

alleging that 8 chief justices of India were corrupt, but also in its narrowest

terms. The subversion of law is to such

an extent that even when no information has been provided the information

commissioners brazenly record that all available information has been provided

and close the case.

Let me narrate an example.

I was travelling by train

to Thiruvananthapuram. I had only an RAC (Reservation against Cancellation)

ticket but I was the first on the RAC list. That meant even if there had been

just one cancellation I should have got a berth. However, even after one hour

of the departure from the train there was no allotment of berth. So, when the

TTE (Travelling Ticket Examiner) came around next time, I approached him with a

request that I should be given a certificate that I had not been allotted a

berth. The reason was simple. The RAC tickets are issued against full cost of a

sleeper ticket, but when you are not allotted a berth it turns out to be just a

sitting accommodation in the Sleeper Coach. So I wanted to claim refund of the

excess cost and if denied follow it up with appropriate authorities. Suffice to say that the TTE did not give the

certificate sought but allotted a berth within the next 15 minutes.

Now, the issue could not

be left at that. The objective of the RTI Act is to contain corruption and I

wanted to check if anybody else had been allotted a berth before me (a sign of

corruption, if not in its narrowest sense, surely in its widest sense). So I

sought copies of the reservation chart with the data updated by the TTE. Horror of horrors, the public authority, that

is the Southern Railway Divisional Office at Thiruvananthapuram, demanded Rs 750/- per PNR number against Rs 2/- per page prescribed in the RTI Rules

of the Central Government. The 2nd appeal filed on 16/04/2014 was dismissed

by the information commissioner, Bimal Julka, on 14/07/2016.

Section 219 of the Indian

Penal Code does provide for prosecuting such public servants and when convicted

they are liable to imprisonment for 7 years. Just imagine what would happen if

each information commissioner is prosecuted for every wrong verdict he

delivers. But who will prosecute these delinquent and corrupt information

commissioners when the judiciary takes decades to give verdict even in rape and

murder cases?

There is also this

unwarranted hurdle of seeking permission for prosecution of these treacherous

public servants from others of their ilk. Just imagine the ridiculousness of

the public needing to take permission from a public servant to prosecute

another public servant. And even in the rare cases you get the permission, the

public servant will defend his case at taxpayer’s money where as the

complainant will have to drain his own resources. Great level playing field,

isn’t it?

There have been cases

where PIOs penalized by the information commissioners have appealed to the high

courts, at taxpayers’ cost. In one such case at least, a high court had ruled

that the appellant (the penalized PIO) will have to bear the expenses himself

and tax payers’ money cannot be wasted on it. But, has any competent authority

followed the logic and incorporated it in their rules? To the best of my knowledge and belief, it is

a definite no.

The RTI Act is a very

simple and unambiguous law. It, to my mind, is the only pro-democracy and

citizen friendly law in the country. It empowers the President (Sec 14(3)(d))

and the Governors in the respective

states (Section 17(3)(d ))to order removal of information commissioners who

are, in their opinion, unfit to continue in office by reason of infirmity of

mind or body. But what do you do when

these high offices act only as post offices? Let me narrate two instances.

A judgment published as

2004(3) KLT 1073 had observed that the President of the Kerala State Consumer

Disputes Redressal Commission, a former judge of the same court, had mislead the court in the matter of the

President having declared holidays for the Commission in line with the holidays

declared by the High Court. Since no action for perjury had been initiated by

the court a complaint was filed with the National Consumer Dispute Redressal

Commission by an umbrella organization of consumer rights activists, Save

Consumer Courts Action Council. Later an application under the RTI Act was

submitted to get information on action taken on the complaint. The reply advised the matter to be taken up

with the Government of Kerala. Since

that could not be accepted as an action taken on the complaint the matter

finally landed with the Chief Information Commissioner, Wajahat Habibulla. He, without

applying his mind (not unusual with our babus), sent it to the Kerala State

Information Commission. The fiasco was brought to his notice and the appeal was

resubmitted. He, shockingly, forwarded it also to the KSIC. A complaint was

submitted to the President to remove him under Section 14(3)(d) of the RTI Act.

An application under the RTI Act for information on action taken revealed that

it had been forwarded to the Department of Personnel and Training for action at

their end and informing the complainant.

Similarly, a complaint was

submitted to the Chief Minister of Kerala listing a number of defects and

deficiencies in the functioning of the KSIC and requesting for action under

Section 26 and 27 of the RTI Act. Of these, Section 27(2)(e) and (f) empowers

the competent authority to prescribe the

procedure to be adopted by the State Information Commission in deciding the

appeals and any other matter which is required to be, or may be prescribed.

This was important since the Commission was not even disposing of complaints

and appeals on a first come, first served basis, leave alone directing

delinquent PIOs to provide the information sought or penalizing them, as

mandated by the law. Unfortunately,

after persistent follow up the only response received was from the Department

of General Administration stating that since the Information Commission was an

autonomous entity the Government cannot interfere in its functions.

Can one imagine that there

can be chaos even in the matter of language used? Section 6(1) of the RTI Act

states that A person, who desires to

obtain any information under this Act, shall make a request in writing or

through electronic means in English

or Hindi or in the official language

of the area in which the application is being made. Now, should there be

any doubt about the language in which appeals are to be submitted or replies

are to be given? Just imagine a citizen from Delhi seeking information from a

public authority in Kerala and applying in English and getting a reply in

Malayalam. In any case, we are following a three language formula for our high

school education and no public servant handling documents can be expected to be

having education less than SSLC. But even in fully literate Kerala, it is

common experience that most applications/appeals in English are replied to in

Malayalam.

The malicious nature of

functioning of the public authorities can be seen even in quoting the

references to communications from the applicant /appellant. From PIOs to the

Secretary of the Commission, they will only refer to the date of the

application/appeal, sometimes not even the date mentioned in the document but

the date of its receipt by the PIO/appellate authority, whereas they would

refer to the complete file number and date of the communication from public

authorities. (See Screenshot-6) Even specific requirement of quoting the file

number is maliciously neglected by the PIOs and the appellate authorities.

The latest scam in the

matter of implementing the RTI Act in Kerala is that the KSIC has devised a

new, illegal and abhorrable means of disposing of complaints and appeals. One

fine day the appellant gets a letter from the commission just referring to the

date of submission of application and the public authority and seeking to know

if the contentions averred in the appeal are persisting and if persisting it

should be intimated to the Commission within 10 days, failing which the appeal

would be closed. Adding insult to injury, on the letter head will be given an e

mail id that does not work either.

There is more to the

methods by which this simple pro-democracy, citizen friendly law is being

subverted by the public authorities, including the information commissions and

the courts. More on this later.

P M Ravindran/ raviforjustice@gmail.com 05 December 2022

Screenshot-2. Disclosure under Sec 4(1)(b)(x) of the RTI Act by the Central Information Commission as on 14/05/12, accessed on 19/01/2014.

Screenshot-5.

Disclosure under Sec 4(1)(b)(x) of the RTI Act by the Central Information

Commission as accessed on 04/12/2022

Screenshot-5.

Disclosure under Sec 4(1)(b)(x) of the RTI Act by the Central Information

Commission as accessed on 04/12/2022

No comments:

Post a Comment